OVER THE past decade, Russian President Vladimir Putin has extorted fealty from his neighbors by using energy, particularly natural gas, as a political cudgel. In 2006 and 2009, Gazprom, the Russian state gas monopoly, suspended exports to Ukraine, demonstrating its willingness to withhold fuel from millions of customers to push them around. Now, in the tensest conflict yet between the two nations, Russia is threatening to boost the price Ukrainians pay for gas imports.

This behavior has boomeranged to some extent. Along with other developments in world energy markets, Russia’s subordination of economic considerations to political ones has given both Ukraine and the West incentive to diversify their supply sources, which has increased their leverage. That should help Ukraine and the European Union resist Russia’s aggression now and do more to free themselves from Gazprom’sNot that it will be easy. Europe still imports massive amounts of Russian natural gas, which accounted for about a third of European consumption last year. It’s much cheaper to transport gas via pipeline than to liquefy and ship it, which gives Russia’s product an advantage over some competitors. But the continued development of alternative gas suppliers such as Qatar and Norway and of European infrastructure to accept liquefied natural gas (LNG) have given European importers more power.

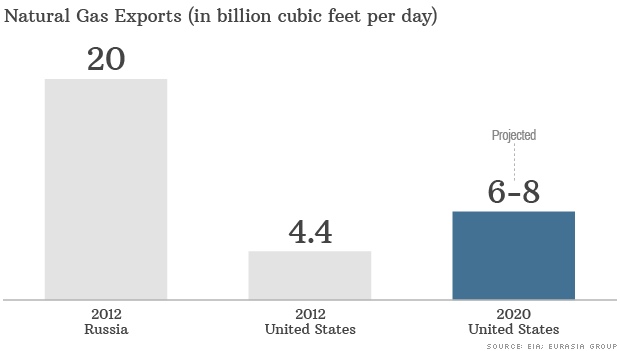

America’s natural gas boom helps, too. Once thought to be a permanent importer of gas, the United States is now producing huge amounts of the fuel, to the point that energy firms want to export it. U.S. exports could reduce Russia’s leverage further. But simply the withdrawal of the United States’ once-hefty demand from the global market already has helped.

As long as Europe sticks together, Mr. Putin cannot be confident of a favorable outcome should he seek to provoke a gas crisis. Large stores of natural gas in Central and Eastern Europe, including in Ukraine, can keep energy flowing for quite a while — several months, in Ukraine’s case — if the Russian supply is diminished or cut off, by Mr. Putin or by sanctions. Pipelines crossing the region can transport gas east, from well-supplied European markets, as well as west from Russia. Russia’s export-dependent economy, meanwhile, would pay a dear price for a broad or sustained slowdown in sales.

In the long term, Europe and Ukraine should continue to make their energy markets more flexible. Ukraine should consider building an LNG import terminal on the Black Sea, and the country must clean up its notoriously corrupt energy production sector. The nation has sizable gas resources; wise economic reform would ensure that the prices Ukrainian energy producers get reflect market fundamentals, which would encourage energy development. Chevron and Royal Dutch Shell, which are hoping to tap Ukrainian shale gas, could deliver significant amounts by 2020.

The new Ukrainian government should embrace that deal and commit to attracting more Western investment. Western governments, meanwhile, must not waver in standing with their Ukrainian neighbors.

grip in the future.