NAZI U-boats had a deadly hunting season in the Gulf of Mexico in 1942-43, prompting American military planners to put safety first when working out how to ship fuel for the liberation of Europe. Seven decades later, the Sweeny refinery in Texas is still safely (and oddly) inland, out of range of German guns—and playing a part in the rebirth of America as an exporter of hydrocarbons.

At Sweeny and the terminal it serves, Freeport, Philips 66—America’s sixth-biggest listed firm—is spending a combined $3 billion on new facilities to export liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), and on an installation to process natural gas liquids (NGLs). These two products of gas wells are versatile fuels as well as valuable raw materials for petrochemicals.

Further west along the coast at Corpus Christi, a planned export terminal for a third hydrocarbon product, liquefied natural gas (LNG), has become the fifth such project to gain regulatory approval. The owner, Cheniere, is spending $30 billion on this plant and another at Sabine Pass, on the Louisana-Texas border.

These schemes exemplify a big switch in America’s energy industry. The terminals had been designed to handle imports, at a time when the glory days of American oil and gas seemed gone for good. Lingering memories of those days, and particularly of long queues at filling stations after the oil shocks of the 1970s, still leave politicians and the public twitchy about exports of energy products.

Crude-oil exports are mostly banned under a law dating from 1975; LNG can be sold without a permit only to the few countries with which America has free-trade agreements. Keeping precious hydrocarbons at home means low prices and stable supplies, the thinking goes.

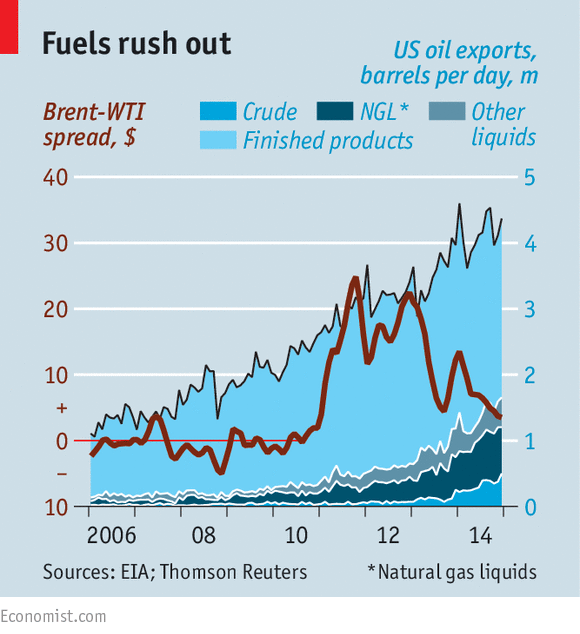

Yet America already sends plenty of energy abroad (see chart). It is the world’s largest exporter of refined products such as diesel, petrol (gasoline) and aviation fuel (kerosene). It is a net exporter of coal and this year will become a net exporter of gas, too. American waterborne LPG exports have overtaken those of many big Arab producers and the country will surpass Qatar to become the world’s largest by 2020, says IHS, a consulting firm.

Many factors have fuelled the boom. American coal is cheap. Oil and gas production have boomed thanks to hydraulic fracturing (fracking) and horizontal drilling of shale rock. A captive supply of cheaper oil and gas at home has helped American refineries, inefficient though they are, to make and export products that compete keenly against better-run rivals. European refiners, in particular, are howling at that.

America is already an exporter of crude, too, though that is a well-kept secret. This is chiefly thanks to “swaps”, exports of oil that are balanced by imports of it. The law permits such exchanges on grounds of “convenience or efficiency”. A lot of American crude is already swapped for Canadian. And now Mexico’s state-owned oil company, Pemex, has asked the US Commerce Department for permission to import 100,000 barrels a day of light crude in exchange for the much heavier grades of crude it sends in the opposite direction (in far larger volumes).

Exporting more light crude could be a lifeline for beleaguered frackers, whose business has been overturned by the recent steep fall in the oil price. The bulk of the increase in their production is light crude, but American refineries are still mainly configured to deal with the heavy stuff—a legacy of past reliance on imports from Latin America and the Persian Gulf.

Boring and drilling

Legally speaking, the line between light crude and refined products is blurry. When oil is “stabilised”, for example—heated to make it safe to transport via pipelines—that can make it count as a refined product, suitable for export. The administration has also exempted a kind of ultra-light crude called condensate from the export ban.

Enterprise Products Partners, a pipeline firm, has recently agreed two condensate export contracts for 1.2m barrels a month. Shell has won approval to export the stuff; ConocoPhillips is seeking a licence and BHP Billiton, a mining company, has sold at least two cargoes. Vague new rules issued last year create more scope for exports.

The weak oil price has clouded this sunny landscape. Investment decisions made a year ago now look questionable. The once-juicy price gap between a barrel of West Texas Intermediate (America’s benchmark) and Brent (the closest the industry has to a world oil price) has shrivelled (see chart), along with the scale of the incentive to sell American oil abroad.

Other effects of lower prices are more helpful. Americans should worry less about the cost of filling their cars’ tanks. That ought to weaken the main protectionist pressure which constrains exports.

Allowing oil exports would raise production at home, helping local drillers. It would also put more oil on world markets, cutting the price. That would eat into the margins of refineries, but it would be a boon to consumers everywhere—and perhaps to American motorists, too, whose petrol prices are set on global, not national, markets. Even if crude-oil exports did not cut the costs of petrol at the pump, they would not raise them.

Vaclav Bartuska, the Czech Republic’s energy envoy, is in Washington, DC, this week urging American policymakers to liberalise energy exports for another reason: to safeguard allies under pressure from Russia. America should join the small club of “boring” oil exporters, otherwise known as democracies, he says. If freeing crude exports makes America richer, its allies stronger, its foes weaker and the world safer, what stands in the way? Having foiled the Nazis, Texas may yet have a role to play in thwarting the Kremlin.